What is a Co-op?

The International Co-operative Alliance defines a co-op as an "autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically-controlled enterprise"[1]

Cooperative identity, values & principles #

Co-ops often follow what are known as the Rochdale Principles, a framework for putting these values into practice.

The principles were developed by the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, an English co-op formed in 1844[2]. The BSC apartment complex is named after them.

The Rochdale Principles have changed over time. For example, the 1937 version stated that organizations should practice "political and religious neutrality." This is no longer the case. However, membership is to be "open [and] voluntary."[3]

Principles of Co-operation #

Collective ownership and co-operation is not a new idea, and certainly not one that has originated from europe. Indigenous societies in north america have long practiced forms of collective stewardship and organization.

Many settler-colonial democracies, such as the u.s., have tried to violently eradicate ways of living and knowing outside capital and accumulation.

According to co-operative scholar Jessica Gordon Nembhard, "Even though separated from their clans and nations in Africa, enslaved as well as the few free African Americans continued African practices during the antebellum period — cooperating economically to till small garden plots to provide more variety and a healthier diet for their families."[4]

After chattel slavery was abolished, many agricultural co-operatives sprung up. Former slaves pooled their resources to own the land and means of production, instead of sharecropping under white landowners.

We find that the spirit of revolt which tried to co-operate by means of insurrection led to widespread organization for the rescue of fugitive slaves among Negroes themselves, and developed before the war in the North and during and after the war in the South, into various co-operative efforts toward economic emancipation and land buying. Gradually these efforts led to co-operative business, building and loan associations and trade unions. — W.E.B. Du Bois, 1907[5]

Co-ops, Capitalism, and the Economy #

Co-ops exist all over the world. The ICA estimates that over 1 billion people are members of a co-operative.[6] These take many different forms.

Producer-Owned Co-ops #

You may be surprised to learn that Land O’Lakes butter and Sunkist citrus products are distributed by co-ops.[7] That means Sunkist, the largest fresh produce shipper in the u.s., is a co-op.

These growers formed their co-op in order to increase profits. The capitalists — not workers — came together to pool their resources into collective marketing campaigns and collectively fight against labor organizing.[8]

Thus, co-ops are not inherently anti-capitalist or oppositional to the global economy. Co-ops are an integral part of the global economic system, and have been created in virtually every industry, sometimes for the purpose of increasing a shared profit.

Consumer-Owned Co-ops #

Consumer co-ops are probably the type of co-op most people are familiar with. This includes grocery co-ops and banking co-ops (credit unions), of which many u.s. cities have at least one. Berkeley used to have the largest consumer co-op in North America, the Consumers' Cooperative of Berkeley, which collapsed in the late 1980s.

Typical businesses exist to produce profit for the owners. Since the shoppers are the owners, consumer co-ops should be able to pass these savings into lower prices for members.

Consumer co-ops typically have some democratic control, where members elect the leadership of the co-op. However, members have more power in some co-ops than others.

Labor is the biggest expense in most businesses, and this sometimes puts shopper-owners of consumer co-ops in an oppositional relationship with employees.

This happened in 2013 at the North Coast Cooperative, a Northern California consumer food co-op. Management brought in a consulting lawyer to "represent" the co-op in negotiations with its workers:

Abetted by their counsel, co-op management made an initial proposal to the union that would reduce employees' medical benefits and their pay step increments ... In addition, management has reduced the work force 20% in the past two years while increasing productivity. This has made work much more intense and stressful.

In this case, workers petitioned members to support higher wages and better working conditions, and gathered 2,000 signatures. 130 members picketed at a board meeting, some asking how much was being paid to retain the corporate lawyer(s). Although they were member-owners, according to an article by Carl Ratner, "management refused to tell the members the exact amount that they paid [the law firm]."[9]

Management may have different interests or values than members and workers within a consumer co-op structure. They could view the membership as an advisory board or suggestion box, while making entirely independent decisions.

In late 2020, the management of Canada's largest retail co-operative, the Mountain Equipment Co-op, sold the entire co-op to a private equity firm without consulting the membership. It is now run as a for-profit company.[10] If a co-op lacks robust mechanisms for members to steer its operation, the whims of officials may be virtually impossible to reverse.

Worker-Owned Co-ops #

Workers, too, have formed their own co-ops. Instead of being owned by shoppers, their organizations are owned and democratically controlled by the workers.

There are a number of prominent worker co-operatives in Berkeley, including the Cheese Board bakery.[11] The Mandela Grocery Co-op in West Oakland is another local worker-owned co-op.

The United States Federation of Worker Co-ops estimates there are more than 500 such co-ops in the country today. When successful, worker-owned co-ops can ensure high pay and offer job opportunities for people who might have difficulty getting positions elsewhere.[12]

Co-ops have also supported or been closely associated with the labor movement. According to Paula Jaramillo, "communal living played an important part in the labor movement throughout the Industrial Revolution and beyond. Many saw the exploitation from landlords and the exploitation from bosses as part of the same struggle. Uniting and cooperating both in labor and housing was a way to retake control and assert self-determination.

"Furthermore, many unionized workers lived together which transformed the domestic sphere into an important political sphere useful for organizing. Some examples in the Bay Area include the Knights of Labor during the 1880s providing housing for striking workers in San Francisco and Oakland. Later on in 1960 the St. Francis Square Co-op was founded, a cooperative where leaders of the International Longshoremen Workers Union lived communally."[13]

Housing Co-ops #

So what is the BSC? See: "How is the BSC different than a landlord?"

Co-ops and Communism #

The Unemployed Exchange Association (UXA) in Oakland was a self-help cooperative organized around reciprocity rather than money. At its peak in the 1930s, the UXA provided food, medical and dental benefits, auto repair and some housing to around 1,500 people. In fall 1932, the police “Red Squad”, who had received information that the UXA was led by “Communists,” raided their meeting and shut them down under the pretext that they were violating ordinances which prohibited the sale of food and clothing from the same store.[13:1]

The UXA, which many BSC members participated in, became a political target of the state. During the cold war, however, some anti-communists began to see co-ops as a possible bulwark against communism in the global south. They wanted to promote co-operative models which emphasized participation in the capitalist economy and downplayed the radical democratic elements.

This [the co-op model] was going to be the third way; it was going to stop communism in other parts of the world. — Robert E. Treuhaft, reflecting on anti-communism in the co-operative movement.[14]

The Berkeley Consumer Co-op grappled with these machinations in the mid-1960s. The board discovered that the National Co-op League, which it paid into, was also "receiving large amounts of money from the CIA through a foundation" — about $200,000 to $300,000 per year — to promote co-ops abroad. However, when board members expressed interest in expanding co-op education within the u.s., they were told it was not possible — a bizarre contradiction that lead to the unraveling of the scandal.[15]

Under the anti-communist Nixon administration of the 1970s, co-ops in the u.s. were systematically undermined and dismantled.[13:2]

Anarchistic Co-ops and Volunteer Collectives #

The co-ops described above often have structures which echo liberal democracies and for-profit/non-profit corporations. For example, they may have a board of directors, who are routinely elected to make decisions on behalf of the membership — the same way representative democracy is set up in the u.s. They may also require that members register in a particular way or pay certain fees to join. These are all true of the BSC.

However, not all co-ops are like this. Some develop informally, existing outside the legal requirements of a corporation, or are legally registered but only as a matter of form. They may not have distinct classes such as workers, managers, or members. These are often called collectives. We have many collectives in the Bay Area. These include the Moments Cooperative in Oakland, the volunteer-run Long Haul collective in Berkeley, and the anarchistic hackerspace Noisebridge in SF.

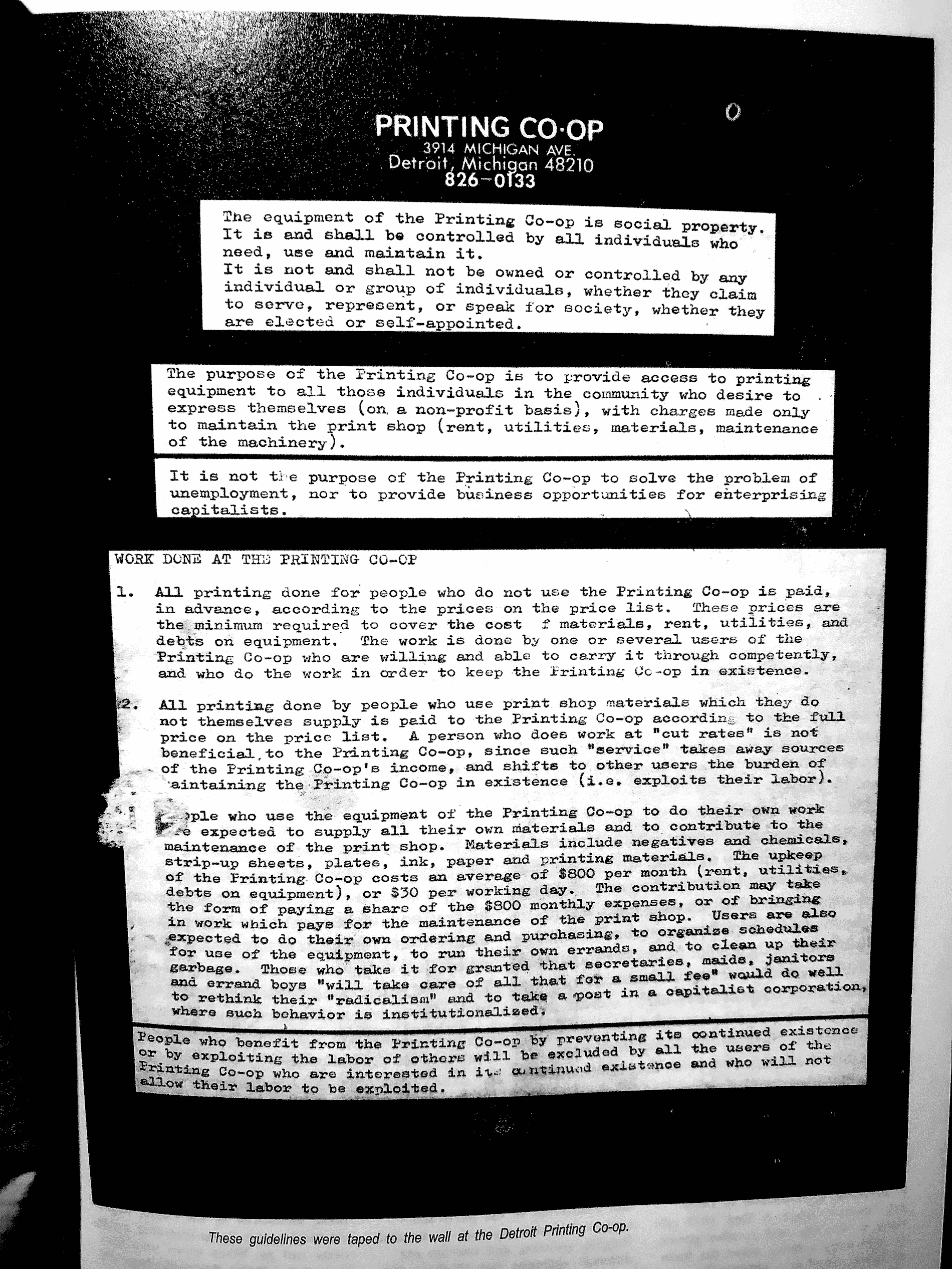

Here's one illustrative example. In the 1960s, anarchist writer and publisher Fredy Perlman started the Detroit Printing Co-op. Rather than forming an elected body of officials to set policy for the co-op and control its resources, the info sheet posted around the facility read:

The equipment of the Printing Co-op is social property. It is and shall be controlled by all individuals who need, use, and maintain it. It is not and shall not be owned or controlled by any individual or group of individuals, whether they claim to serve, represent, or speak for society, whether they are elected or self-appointed.[16]

This contrasts with how we consider some property in the BSC. For example, we may think about an expensive copy machine at Central Office in these terms: "this is BSC property, and board and/or management decides how it is utilized." On the other hand, we may pick up a pot or pan in our room-and-board house and think of it more as social property, rather than something existing within a formal governance structure.

Most of these groups are smaller in size, and often more homogenous; a more formal structure can provide stability and shared terms of engagement for larger and more diverse co-operatives.

Wikipedia, Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers ↩︎

Wikipedia, Rochdale Principles ↩︎

Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice, p. 31 ↩︎

as cited in Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice, p. 27 ↩︎

Richard C. Williams, The Co-operative Movement: Globalization from Below ↩︎

Jeffrey L. Cruikshank, Arthur W. Schultz (2010). The Man Who Sold America: The Amazing (but True!) Story of Albert D. Lasker and the Creation of the Advertising Century. Harvard Business Review Press. p. 114. As cited in Wikipedia, Sunkist Growers Incorporated. ↩︎

Carl Ratner, "A Failure of Cooperative Values at California's Largest Consumer Food Co-op" ↩︎

Leyland Cecco, Members of Canada’s largest retail co-op seek to block sale to US private equity fund" ↩︎

U.S. Federation of Worker Cooperatives, What is a Worker Cooperative? ↩︎

Paula Jaramillo (2015), Communal Living Sketches in Berkeley, FoundSF Wiki ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Oral interview with Robert E. Treuhaft, conducted by Robert G. Larsen for the Berkeley Historical Society (1990), p. 64 ↩︎

"So we had a dozen people abroad selling the co-op idea, and they couldn't afford to send anybody into the South in the United States. Why was this going on? What expertise did we have to begin with, when we were the most backward country in the world from the point of view of co-ops? The Co-op League could never build a co-op movement in the United States. What were they doing in Southeast Asia and South America? So I explored this, and I was familiar with the fact that it was national public knowledge, it was a major public scandal, about the CIA funneling money through foundations. Some of the recipients were student organizations, who were considered anti the most radical students ... I corresponded with some of the people, and Neil Sheehan, a New York Times reporter, finally came up with the information that the Co-op league had been receiving large amounts of money from the CIA through a foundation..." Oral interview with Robert E. Treuhaft, conducted by Robert G. Larsen for the Berkeley Historical Society (1990), p. 77 ↩︎

As cited in Danielle Aubert, The Detroit Printing Co-op ↩︎