Who is the BSC?

Origins of the Student Co-op #

When the BSC was founded in 1933, it was known as the University of California Students' Cooperative Association (UCSCA), and provided low-cost room and board for UC students.

The University of California #

In the first decades of the University of California’s existence, Euro-Americans, largely Protestants, remained the majority. But there were also some mestizos and Black students. By the turn of the twentieth century, there were also East and South Asian students, both visitors and permanent residents.[1]

The University of California was created by settlers. The land the university sits on — xučyun territory — is stolen from Indigenous peoples, specifically the Chochenyo-speaking Ohlone. The settlers accepted this genocide and removal as a necessary condition to grow their university.

Likewise, they took the widespread exploitation of Indigenous, Black, and brown labor in California for granted. While officially having a race-neutral admissions policy, it is little surprise that the UC primarily served Anglo settlers.[2]

By 1933, UC Berkeley had about 12,500 students (compared to almost three times that today).[3] The University of California was not the multi-campus institution it is today, nor were there all the community colleges and Cal State schools we have today.

For students across the state seeking higher education, the town of Berkeley was the place to go.

A Need for Low-Cost Housing #

The co-op grew out of existing student organizations and connections.

One of them was Stiles Hall, a building on the south campus. Closely connected to the UC YMCA, Stiles Hall was like a student union. Because the university did not provide on-campus housing for many decades, arriving students might stop there to get a list of places to find room and board.[4]

Many students involved in these organizations participated in Bible study and Christian ministry. They went to San Francisco for this, where during the thirties they encountered mass labor organizing around socialist principles, and poverty and resistance in Chinatown. These interactions transformed the character of the YMCA and other groups.[5]

The Knights of Labor had provided housing for striking workers in San Francisco and Oakland during the 1880s, and as the Great Depression set in, communal ideas remained at the forefront of Bay Area organizing and thinking.[6]

In Berkeley, the Depression had severely impacted many UC students. Financial aid was insufficient and opportunities for students to earn money were meager. In this environment, organizations like the YMCA became more secular and shifted their work to the "general social and political areas of civil rights and free speech."[5:1]

One Christian missionary, Harry Kingman, became interested in these areas. In 1932, he became the leader of of Stiles Hall and the UC YMCA. Kingman focused intensely on students' economic security.

Harry Kingman observed the day-to-day struggles of students to meet minimal expenses and, out of economic need, the student co-ops evolved, providing inexpensive housing where labor and facilities could be pooled. One staff member, Francis Smart, was assigned specifically to the development of the co-op living group; and Bill Davis, the new Freshman Secretary, actually moved into Barrington Hall, one of the very first co-ops, as a kind of "house father." Thus, from the very origins of the organization now known as the [BSC] ... Stiles Hall was involved.[7]

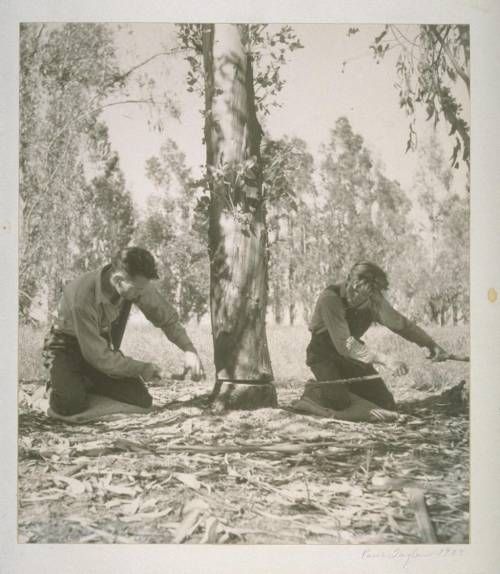

The co-op began modestly, under the wing of Kingman and Stiles Hall, with a boarding house run by Annie Dickson. She rented a large house, shopped, and cooked meals for twenty male students, who each paid $10 per month for room and board. Each student also contributed four hours per week of workshift.

However, the students' goal was to have a rooming house they ran themselves. In preparation to open one in fall 1933, some aspiring co-opers spent the summer chopping wood in Dixon, CA in collaboration with the Unemployed Exchange Association (UXA) to get coupons for produce that could be redeemed during the semester.[8]

The UXA in Oakland was a self-help cooperative organized around reciprocity rather than money. At its peak, the UXA provided food, medical and dental benefits, auto repair and some housing to around 1,500 people.[6:1]

By the fall, with rents from members and a $650 loan from the UC Faculty committee, the first co-op house was leased and opened with several live-in house officials and staff.

The BSC and Racial Non-Discrimination #

In 1933, students concerned with the availability of low-cost housing and the social conditions of a nation in the midst of a severe economic depression created the first housing cooperative open to all races.[9]

In 1926, Berkeley was 96.8% white. A census recorded 507 Black people and 1,333 people of Asian descent.[10]

As the university claimed race neutrality in its admissions, the city of Berkeley and the university's on-campus services did not. Non-white students faced racism and hostility in finding housing, food, and jobs. Many Berkeley restaurants only served white people, and discrimination was routine in student boarding and rooming houses.

The city itself was de-facto segregated, with neighborhoods such as Claremont marked by pillars which explicitly marked them as "sundown" white-only areas.[11]

Into the 1950s, the university dorms were segregated as well. Black students were excluded from the campus jobs many others relied on.

The co-op did away with the segregation of the university and proprietors, though it remained a predominantly white group, mirroring the university as a whole. A commitment to liberal politics and "the spirit of magnanimity," a term from Stiles Hall, led them to practice non-discrimination.[12] Stiles Hall was nationally regarded as the most integrated YMCA in the nation at the time. It had non-white student officers, and intervened against anti-Black Berkeley homeowners on several occasions.[13]

"Rochdale principle and common liberal thought required that the co-op practice racial desegregation in the house." Nonetheless, it was noteworthy when a Black student actually applied to become a member in the first Barrington house.[14] The co-op was a very important resource for students of color, and one which they quickly took a role in architecting.

Changing Berkeley, Growing Membership #

The city of Berkeley and the Bay Area was growing and changing.

About two decades after the BSC's founding, after years of the "Great Migration" and immigration from China and Japan, 13,289 Black people and 4,248 people of Asian descent lived in Berkeley.[10:1]

Dating from its colonization as a white homesteader town, Berkeley's structures were mostly old houses. These were converted — often badly, given the lack of construction materials during wartimes — into apartment buildings or boarding houses for workers and students.

UC avoided building and running its own housing for decades, so the student co-op filled the gaps. Recognizing this, UC faculty and leadership were supportive of the co-op's early development.

In 1935, UC Dean of Women Lucy Ward Stebbins worked to secure a $3,000 loan to the co-op, the deposit it needed to open the first women's hall. Stebbins opened in 1936, bringing the co-op membership to more than 400 people.[15]

This rapid expansion led to the establishment of a Central Kitchen in 1938, at Oxford Hall, and the development of connections between the independent houses, such as a USCA-wide newsletter.

In the early 1940s, one of the USCA's early houses, Sheridan, eclipsed the frats as a "power base" for UC student politics.[16]

World War II #

A building which had housed the Japanese Students Club was abruptly vacated in 1942 when the u.s. government began forcibly relocating Japanese americans in California to concentration camps. The student co-op took over the building lease and used it to house male students at first, then eventually women.[17]

While young men were deployed in the military for World War II, the co-op membership and leadership became mostly women.[18]

Post-War Boom #

After World War II, enrollment at universities skyrocketed across the country. The GI Bill of 1944 changed higher education from "a limited privilege to a generalized public expectation."[19]

The BSC purchased the former Cloyne Court Hotel and Ridge House during this time, to convert to co-ops.

By the mid-1950s, UC Berkeley was enrolling thousands more students, most of them men. In what had historically been a majority white and Protestant university, many more Black, Latinx, Catholic, and/or Jewish veterans were becoming students.

The university gave up their long-standing reluctance to operate student housing, and set out to build high-rise dormitories (the "Units"), which they described as "elevator-type living centers." They razed huge swaths of existing housing on southside in preparation to build six complexes, though they only built three.[20]

Upheaval and Renewal #

In a prelude to the decade to come, politics seized the campus in the 1950s over California's anti-communist loyalty oath.[21] The USCA was faced with potentially losing its tax-exempt status if it refused to sign a restrictive loyalty statement to the state and u.s. governments.

Bob Shepherd wrote in a 1954 issue of U.S.C.A. News, of which he was a co-editor:

We count among the majority of our members science majors — students of chemistry, physics and engineering who hope in the next four years to be working for the government. Quite a few are already working in the government radiation, atomic energy, and microwave labs here on campus. A goodly number are looking forward to steady positions with state or federal offices such as the F.B.I.... few, if any of us, could afford to be labeled as members of a subversive organization.[22]

The question was brought to a member referendum, and more than 60% of members voted to sign the oath.

Then, as now, consensus was absent on a core question. Did the co-op stand as an alternative to exploitative ways of life, and as such should take a stances against forms of state repression? Or was it merely, as the title of a comprehensive history of the USCA asks, "a cheap place to live"?

The 60s and 70s #

These decades were transformative for Berkeley and the world. Berkeley went from a quiet college town to one of the centers of diffuse social uprisings. These mass social movements included the Free Speech Movement, the hippie counterculture, an increased interest in communism and anti-capitalist insurgency, feminist organization and direct action, and the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF).

"During our 10 week [TWLF] strike, I would go to the four co-ops on Ridge Road during dinner and address the students about the strike."

— Clementina Duron[23]

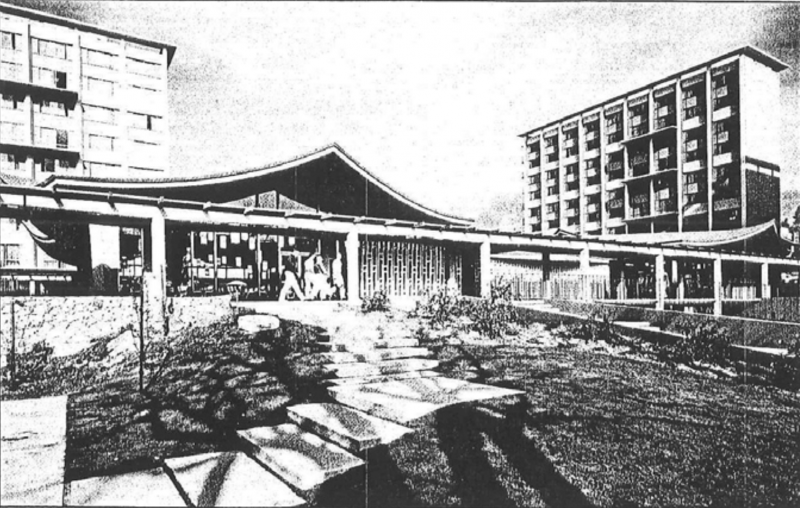

During this time, the co-op built and opened Ridge Project, a brutalist high-rise that was a dramatic depature from the houses. It was notable for being the first co-op to house both women and men. Ridge Project, now known as Casa Zimbabwe, continues to house the Central Office and Central Food and Supplies.

The BSC also leased one of the university's southside tracts to build the Rochdale Village apartments, creating some of the only affordable and accessible apartments in the area.

Third World Liberation #

Full article: Third World BSC Member Activism

“Racism in the Co-op is not just another bullshit issue that can be solved by creating a few token C.O. positions and then forgetting about the problem because it really exists: if we are indeed the liberal non-racist organization we claim to be we must support a conscientious program - an affirmative action program - to use the Co-op to bring about a real change in the conditions in which we are living.”[24]

In the mid-1970s, as an outgrowth of the work of the TWLF, Black and Brown students began organizing for a co-op that centered people of color. These students worked to create compensated positions to recruit BIPOC students and structurally support them in the houses.

Rapid Expansion #

After the 1960s, the fraternity and sorority system collapsed as students turned against it. As a result, "the co-op was able to obtain three former sororities at a reasonable price." These included Davis House, Andres Castro Arms (Now the Person of Color Theme House), and Wolf House.[25]

It would also purchase during this time the buildings which became Lothlorien, Kingman, and Le Chateau.

Embers of Change #

As an explosive era ended, the co-op emerged as a major student housing provider with new apartments and a highrise communal dorm to show for it.

Two questions have animated the recent history of the BSC: Who lives in these co-ops? And who runs them?

Barrington Closure & Squat #

Full wiki article: Barrington Hall

Barrington Hall, a large and long building on Dwight Way, was one of the BSC's earliest purchases, in 1938. It began as a men's house known for patriotism and support of Cal football.

By the 1980s, however, it had become a center of the punk scene, leftist political organizing, and the counterculture.

Drug use and the house's open door tendencies soon drew the ire of the BSC management and Board. General Manager George Proper characterized the problems at Barrington as "lawsuit threats, crashers, heavy drug use, health hazards and difficulty filling house contracts."[26]

In 1990, co-op management encouraged members to vote in a referendum to close it for a year for renovations and open it with all-new residents to try to flush out the perceived cultural issues and drug use.

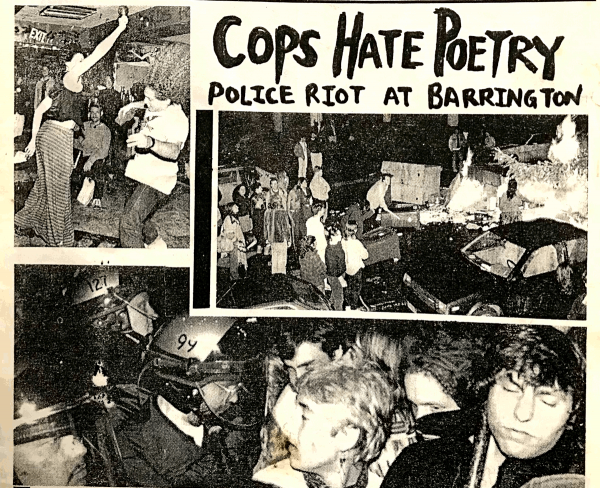

However, some residents squatted the building, hoping to take over Barrington as an independent co-op or reverse the outcome. In March 1990, three months into the squat, police arrived at Barrington intent on extinguishing a poetry event. BSC general manager George Proper directed them to shut it down.[27]

Police stormed the building, and hundreds came out for the ensuing riot. Fires were started outside the building, and the structure and its contents were severely damaged by police and others. Assaults and arrests were primarily targeted at women and the people of color present, who were a small minority of Barrington.[28] The co-op never re-opened Barrington and still leases it to an external landlord.

The Barrington squat, while ultimately extinguished by force, posed serious challenges to the BSC's claims to representative democracy. One alternative newspaper described this tension as:

While the management of the University Student’s Cooperative Association wants it’s tenants to believe that they live in cooperatives and that “you own it,” the Association is better described as a representative liberal land-management corporation with some cooperative features.[29]

The Barringtonians understood that the BSC is incorporated as a non-profit corporation, and has a hierarchical structure similar to medium-sized businesses or charities.[30]

The exception to this is that the ultimate governing body of the organization, the Board of Directors, is almost entirely members elected from their units. The Board has the power to change the structure of the organization, and members have some mechanisms to hold their Board accountable.

Theme Houses #

To accommodate members' vision for better living experiences, the BSC has opened or converted several theme houses.

The first was African American Theme House ("Afro House"), in 1997. Oscar Wilde House, with a queer theme, opened in Spring 1999.[25:1]

In the 2010s, BSC management and Board raised concerns about a drug culture at Cloyne and proposed interventions similar to the ones which had been attempted on Barrington. In 2014, members voted at Board to re-theme Cloyne as the substance-free, academic theme house.[31]

In 2016, the BSC converted Andres Castro Arms to be the Person of Color Theme House, in order to "create a safe space and improve access for POC students, provide additional leadership opportunities, and demonstrate the BSC’s commitment to inclusion and diversity."[32]

The BSC Today #

Membership Now #

As it has been since its founding, the overall BSC membership is mostly UC Berkeley students. As of 2021, less than 5% of BSC members are community college (or any non-UC Berkeley school) students.

About 54% of BSC members are low-income, 45% are first-generation, 22% have disabilities, and 13% are transfer students.[33]

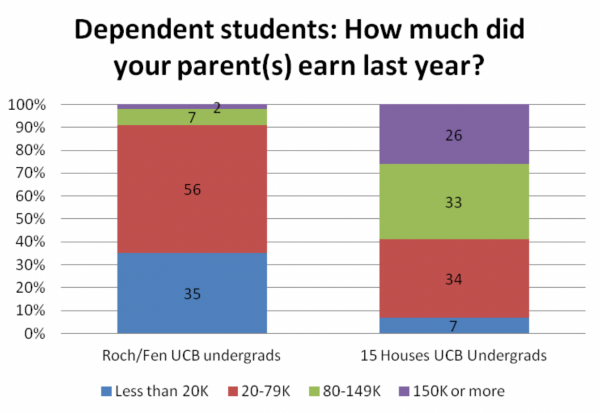

The BSC conducted a demographic survey of the membership in 2012, which proved what is widely known — the co-op houses are whiter and wealthier than the Rochdale/Fenwick apartments. While the apartments are up to 80% Latinx and low-income, the houses remain much less so.

Save Rochdale! #

In 2012, the university looked to take Rochdale away from residents' control by not renewing its lease. A campaign was organized to Save Rochdale, or "Save the Roach!"

Members signed petitions, filmed videos, wore t-shirts around campus, and organized a local, vital campaign within the apartments to keep Rochdale under member control.[34]

Co-opers Alex Ghenis and David Velasquez wrote in the Daily Cal:

Rochdale is the best option for students with disabilities. For students on Supplemental Security Income (SSI) who require a roll-in shower, Rochdale and neighboring (but more costly) Fenwick Weavers Village present the only realistic housing options near campus ... Furthermore, a vibrant community has formed at Rochdale that fosters activism and awareness. For example, approximately half of Latino student advocacy group Hermanos Unidos' leadership lives at Rochdale.[35]

Economics #

Seismic retrofits, and maintaining and upgrading the co-op's aging properties, have been major expenses during this time. Many large houses such as Cloyne and CZ have been retrofitted for earthquake safety, though the Rochdale and Fenwick apartments have not as of 2021.

Defining "Student" #

Since the BSC's founding to serve University of California students, a robust network of community colleges has been established and most students pursue "non-traditional" education. However, the BSC has generally not been a housing provider for these Bay Area students.

The families of university and community college students, student parents, and students with partners may find it difficult to live in the BSC due to strict eligibility requirements and/or being unaware of it. The BSC is not widely known to the public; most people continue to find out about the co-op through word of mouth.

Mutual Aid #

One recent change in the BSC is a formalization of units' support of mutual aid work in Berkeley.

Food Not Bombs had long cooked out of Lothlorien, until they were banned by senior management in 2019.[36]

When the COVID pandemic disrupted FnB's volunteer cooking schedule, two BSC houses, CZ and Cloyne, volunteered to take over cooking for two weekly meals to be distributed at People's Park.

In late 2020, the BSC passed a proposal to officially support this work. The Board allocated funds for community support and to pay participating members hourly wages.[37]

John Aubrey Douglass (2007), The Conditions for Admission: Access, Equity, and the Social Contract of Public Universities, p. 74 ↩︎

The university did not collect regular demographics on the student body until the 1960s. ↩︎

"Enrollment," The Centennial of The University of California, 1868-1968. "Fall 2020 Enrollment," UC Berkeley Quick Facts, accessed 12 Feb 2020. ↩︎

Frances Linsley (1984), What Is This Place? : An Informal History of 100 Years of Stiles Hall, p. 9 ↩︎

Frances Linsley (1984), What Is This Place?, pp. 19, 63 ↩︎ ↩︎

Paula Jaramillo (2015), Communal Living Sketches in Berkeley, FoundSF Wiki ↩︎ ↩︎

Frances Linsley (1984), What Is This Place?, pp. 19, 64 ↩︎

Guy H. Lillian, III, Cheap Place to Live, in The Green Book, p. 8-9 ↩︎

John Aubrey Douglass (2007), The Conditions for Admission: Access, Equity, and the Social Contract of Public Universities, pp. 72-73 ↩︎

George A. Pettitt (1973), Berkeley: The Town and Gown of It, p. 170 ↩︎ ↩︎

Robert Gammon (2017), "Hidden Monuments to Racism," East Bay Express ↩︎

Frances Linsley (1984), What Is This Place?, p. 68 ↩︎

Galen M. Fisher, [Citadel of Democracy](http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001400819|Citadel of Democracy), pp. 23-27 ↩︎

Guy H. Lillian, III, Cheap Place to Live, p. 12 ↩︎

Guy H. Lillian, III, Cheap Place to Live, pp. 23-24 ↩︎

Guy H. Lillian, III, Cheap Place to Live, p. 16 ↩︎

After the war, the building was returned, then later purchased. It is now known as Euclid Hall. Guy H. Lillian, III, Cheap Place to Live, p. 33-34, 43, 91-92 ↩︎

Guy H. Lillian, III, Cheap Place to Live, p. 32 ↩︎

Milton Greenberg (2004), "How the GI Bill Changed Higher Education," Chronicle of Higher Education ↩︎

Page & Turnbull, Inc. (2013), UC Berkeley Unit 3 Housing Historic Resource Evaluation, p. 21 ↩︎

Guy H. Lillian, III, Cheap Place to Live, p. 46 ↩︎

Guy H. Lillian, III, Cheap Place to Live, p. 47 ↩︎

Clementina Duron, "I Am Who I Am Because of the Third World Strike," in Power of the People Won't Stop. Published by Eastwind Books of Berkeley ↩︎

BSC, "Our History" ↩︎ ↩︎

David Tobenkin, "Barrington Closure Threat," USCA Alumni News, date unknown ↩︎

Krista Gasper (2002), "Counterculture's Last Stand" in The Green Book, pp. 147-150. ↩︎

"People of Color Under Attack," Slingshot, Barrington Issue, March 8, 1990 ↩︎

"University Students Cooperative Association: Doesn't Look Very Cooperative to Me," Slingshot, November 1989 ↩︎

Joel J. Rane, who lived in Barrington from 1984 to 1987, characterized this as: "My primary contribution to the USCA was writing a check for room and board twice a semester." See Joel J. Rane, "The Fall of Barrington Hall" ↩︎

Chloee Weiner (2014), "Cloyne Court to become substance-free; only 1 current member may return in fall," The Daily Californian ↩︎

Emery Martinez (2019), "Prioritizing the Recruitment and Retention of Low-Income and Marginalized Students," Cooperatively Yours Newsletter, Fall 2019 ↩︎

SaveRochdale YouTube ↩︎

Alex Ghenis and David Velasquez (2009), "Rochdale: More than a Lease Issue," The Daily Californian ↩︎

Personal knowledge of author ↩︎

BSC Mutual Aid/Survival Programs proposal approved by Fall 2020 Board ↩︎